Published 14:18 IST, April 9th 2024

Airbus obsessives have a shaky grasp of history

Airbus – whose over 50-year history has encompassed public and private owners in major European economies, makes for an appealing template.

- Republic Business

- 6 min read

No plane no gain.

Suddenly, everyone wants to be like Airbus. In recent months, Renault CEO Luca de Meo has called for an “Airbus of autos” to face down the threat to European carmakers from Chinese electric vehicles. In March, the boss of German utility E.ON was fielding questions about the merits of a pan-European mega-utility that could be the “Airbus of energy”. Military specialists antsy about Europe’s highly fragmented defence industry have even been pondering an “Airbus of defence”. That raises two questions – what this outbreak of sloganising actually means; and whether any of the new Airbus obsessives know the full extent of its tortuous back story.

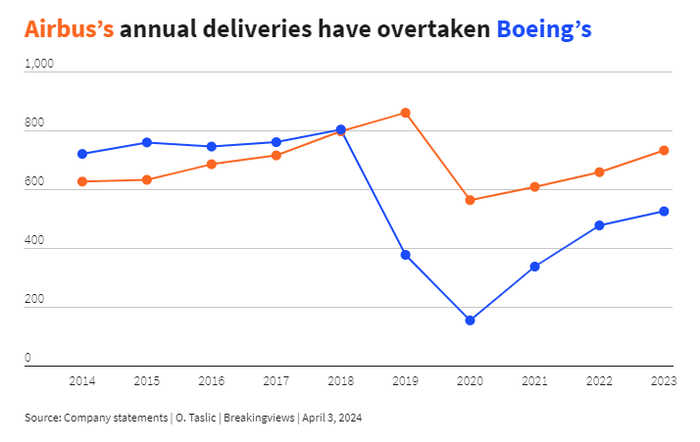

It’s certainly true that the 2024 incarnation of Airbus is flying high. The $140 billion pan-European planemaker’s orders and profits are taking off amid turbulence at U.S. rival Boeing. The company led by CEO Guillaume Faury has seen commercial aircraft deliveries outpace its U.S. rival every year since 2019. Consolidated net income for 2023 came in at 3.8 billion euros while Boeing suffered a roughly $2 billion net loss. Airbus’s year-end commercial order backlog of 8,598 planes is over 2,000 ahead of its competitor. A decade ago, the European group’s lead was around 500.

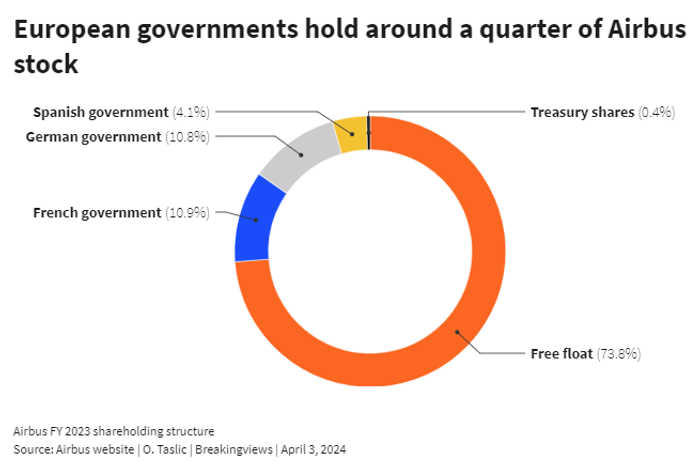

It’s also true that Airbus – whose over 50-year history has encompassed public and private owners in major European economies like Germany, France and the UK – makes for an appealing template. Chinese carmakers like BYD are threatening to eat their European counterparts’ lunch by flooding the market with cheaper EVs. If the likes of Renault, Stellantis and Volkswagen were to merge operations in some sort of Airbus clone, each entity would take on less individual risk and share much-needed expertise, while creating economies of scale in production that might produce a cost-competitive European electric car. Airbus was after all born from a similar state of panic about overseas competition: in the 1960s European aerospace companies feared U.S. rivals like Boeing and Lockheed would send them out of business. At a time when governments are actively meddling in the market, an example of bureaucrats helping to create a globally successful company has clear appeal.

Yet such enthusiasts would benefit from closer study of Airbus’s history. It was only a decade ago that the company assumed its current form, where state and state-aligned investors only hold minority stakes and the board is mostly independent from government. “Airbus Industrie” was formed in 1970 by German and French consortiums with Spanish and British investors coming later. But it did not turn an operating profit until the 1990s, when massive investments and the success of the A320 plane began to pay off. In the early 2000s three contributors – France’s Aerospatiale Matra, Spain’s CASA and Germany’s DaimlerChrysler Aerospace – merged to form the European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company. EADS was to control 80% of the Airbus planemaking outfit, with the UK’s BAE Systems holding the remaining 20%. But the decade that followed demonstrated the difficulties of getting a complex pan-European project off the ground.

The 2000 merger left the culture and processes of what were previously independent national firms largely intact. This compromise reached its nadir in the quest to build the A380 superjumbo, the first of which was delivered in October 2007, 18 months late and several billion dollars over budget. It didn’t help that the A380’s wings were designed and produced in the United Kingdom, fuselage sections came from Germany, and final assembly took place in France before the plane was flown back to Germany to have its body painted and its cabin customised. The real problem, however, was that when problems inevitably emerged in what was a complex design, national rivals did not fully disclose them to management until it was too late. EADS’ practice of appointing joint chief executives like Tom Enders and Louis Gallois – one German, one French – arguably perpetuated the national power struggles.

Airbus eventually sorted itself out: EADS bought out the 20% BAE stake in 2006, streamlining the company, and eventually decided to rebrand as Airbus seven years later. But its current health reflects a host of idiosyncratic features. The gigantic upfront costs involved in making each new aircraft better than the last – with no concrete guarantee airlines will buy them – mean that planemaking tends towards oligopoly. It is also a global market, with airlines around the world choosing from a handful of different models. By contrast, European carmakers already make viable battery-powered vehicles – they just need to be cheaper. Autos are also fiercely location-dependent: Volkswagen is Germany’s bestselling car brand and has obligations to the workers and people of Lower Saxony; French drivers are more likely to buy a Renault. Cross-border M&A would therefore be much harder to pull off, and risk repeating some of the national wrangling that befell EADS in the 2000s.

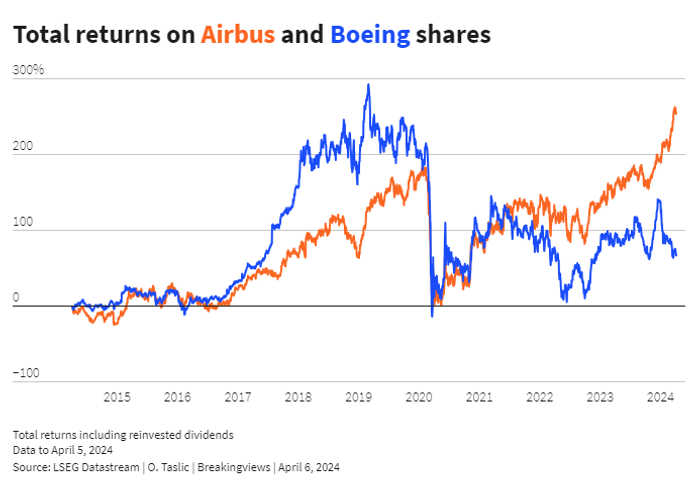

The other powerful support for Airbus’s rude health is the sickness of its main rival. Boeing’s reputation had already been hit by two fatal crashes in 2018 and 2019 that killed 346 people, but it’s now also grappling with the repercussions of a mid-air blowout of a door plug in early January. While Boeing undergoes a radical management shakeup, carriers such as United Airlines are closing in on securing more Airbus jets, Bloomberg reported in March citing people familiar with the matter. As regulators step up factory checks, Boeing may be producing single digits of its MAX aircraft every month, Reuters reported on Wednesday citing industry sources – well below previous monthly output levels of more than 30. Yet despite Airbus’s relative success, the total return on its stock has only exceeded that of its U.S. rival in the last three years.

In other words, Airbus’s current health is a function of over half a century of history and some highly specific circumstances. It might still make sense for European carmakers to collaborate against the threat from Chinese rivals: the Automotive Cells Company, for example, founded in 2020, sees Stellantis, Mercedes-Benz and a subsidiary of TotalEnergies working together to research, develop and produce electric vehicle batteries. Indeed, that may be the kind of partnership de Meo has in mind. If so, he and other Airbus acolytes should probably come up with a better analogy.

Updated 14:18 IST, April 9th 2024