Published 16:20 IST, February 4th 2024

American unions can’t bargain with the inevitable

According to a Gallup poll last September, two-thirds of Americans approve of labor unions, up sharply from a low of 48% in 2009.

- Republic Business

- 5 min read

Picking at scabs. America’s union movement has come a long way since cobblers and leather workers first organized to demand higher wages in 1794. It hasn’t exactly been a smooth journey. That first fateful burst of activity fizzled when factory owners filed a lawsuit that eventually led to massive financial burdens falling on members of the union. Today, unions are protected by U.S. laws that cover collective bargaining. Even so, employers are on track to take the upper hand.

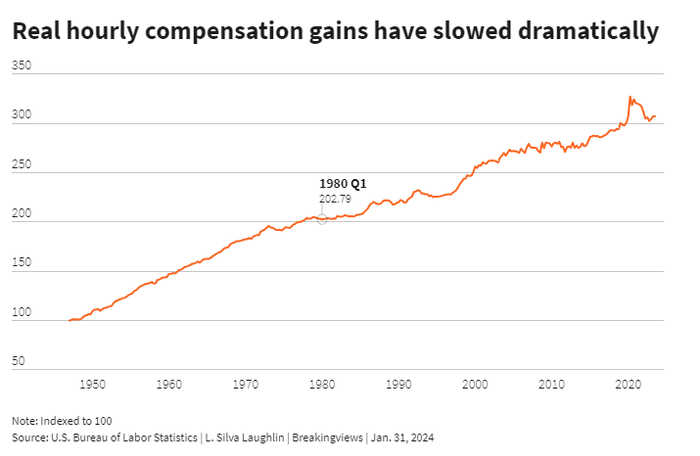

Restive employees felt their oats in 2023, with Starbucks baristas, Hollywood actors and auto-workers at Ford Motor and General Motors among those who downed tools and exercised their right to organize. Even some employees at mega-lender Wells Fargo voted to unionize – something that’s almost unheard of in banking. And there are decent reasons for worker frustration. After a surge in 2020, inflation-adjusted wages have dropped, staging the sharpest fall in nearly seven decades, albeit still higher than they were before Covid-19. At the same time, workers face new personal risks. The number of deaths on the job, for example, were a fifth higher in 2022 than in 2009.

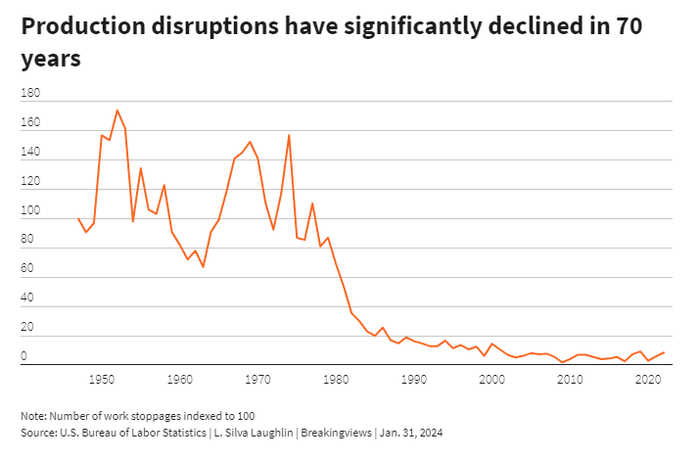

Support for unions – as a concept at least – is still high, too. According to a Gallup poll last September, two-thirds of Americans approve of labor unions, up sharply from a low of 48% in 2009. Yet their actions don’t seem to match their feelings. Participation in unions has actually decreased, as has the frequency of work disruptions. In 2022, the share of workers who were unionized was 10.1%. This was a 23.4 percentage point decline from its post-World War Two peak. For reference, around 67% of the Danish workforce is unionized.

The failure of mor e employees to join unions is a combination of can’t and won’t. Over time, laws have steadily been enacted to make unionization efforts more difficult. The Taft-Hartley Act, passed in 1947, outlawed “closed shop” arrangements, where employers would agree to hire only union members. Around that time, several states adopted so-called “right to work” laws, which prevented employees from being compelled to join a collective bargaining group. In recent years, the adoption of right-to-work laws has increased at a faster rate, and now more than half of all U.S. states have them.

e employees to join unions is a combination of can’t and won’t. Over time, laws have steadily been enacted to make unionization efforts more difficult. The Taft-Hartley Act, passed in 1947, outlawed “closed shop” arrangements, where employers would agree to hire only union members. Around that time, several states adopted so-called “right to work” laws, which prevented employees from being compelled to join a collective bargaining group. In recent years, the adoption of right-to-work laws has increased at a faster rate, and now more than half of all U.S. states have them.

As politics becomes more divisive, unions become a target, because their supporters tend to lean Democrat. According to a poll conducted by think tank GBAO Strategies, roughly 91% of Democrats under the age of 50 support unions while just over 50% of Republicans do. Nearly a third of the Republican workers polled oppose going on strikes. Florida’s Governor Ron DeSantis last year signed a state bill that stops public employers from deducting union dues directly from paychecks, making participation slightly more cumbersome.

For workers, the cost of joining a union may be rising, not just because of moves to make doing so less convenient, but also because employees in some cases run the risk of being penalized for even considering it. While it’s illegal for companies to restrain or coerce people who want to exercise their rights to organize, employers often still find ways to exert soft pressure. For example, grocer Trader Joe’s shut down a store in New York in 2022, and according to the National Labor Relations Board, it was because the employees tried to organize. The store recently opened again, but the people who work there are presumably now less inclined to think about joining forces.

And if an employee is putting their job on the line, they’d want to know that they have a high chance of success if their union does throw down against management. That depends a lot on industry dynamics, though. Successful walkouts came in industries where employees have “striking power.”

Auto workers generally do have that power. Ford has just nine plants in the United States, and making a car takes several days or weeks. Carmakers also sit within a complex network of suppliers and vendors such that disruptions ripple widely and painfully. During last year’s prolonged strikes, Wells Fargo estimated that disruptions at plants this year would cost Ford $320 million of operating income by the end of week three. That’s about 3% of the company’s estimated annual total.

Compare a strike at Starbucks, say. Sure, the coffee chain’s North American stores bring in about $27 billion of revenue annually. But there’s more than 10,600 of them. Not only is it hard to organize a disparate workforce. There’s also little cumulative impact from the latte not poured.

Even in industries where strikes have the potential to cause more damage, demographics might be unfriendly. Auto workers skew older: the average age is 43 versus the restaurant worker, who is 29 years old. Fewer employees above the age of 50 support unions than those under the age of 50, according to GBAO. Political allegiance is shifting too. Affiliates of the UAW used to contribute a negligible amount to Republicans; in 2020, they stumped up roughly a third of what they gave to Democrats, according to OpenSecrets.

That leaves unions in a difficult position, with workers unable to join in some industries, and perhaps less willing even in situations where they might make a difference. For all the efforts of those 18th-century shoemakers, footwear manufacturing ultimately got shipped elsewhere. History is likely to deal U.S. unions a similarly harsh hand.

Updated 16:20 IST, February 4th 2024