Published 15:01 IST, January 24th 2024

Four-day week is clever fix to economic malaise

Figuring out an effective rota system while maintaining the same product and service offering may be difficult, especially at small companies.

Advertisement

Less is more. Working less may be the key to producing more. Companies including $88 billion eyewear giant EssilorLuxottica and $106 billion consumer goods group Unilever are experimenting with shorter working weeks. Pilot schemes have led to revenue increases and sharp declines in burnout rates and churn. It’s a way for CEOs to keep wages in check while making staff happy and freeing them up to spend more.

When tiny Iceland pioneered a four-day working week trial in 2015 that ran for four years and paved the way for a reduction in working hours for most of its citizens, larger countries and big corporations hardly took notice.

Advertisement

The havoc wreaked by the Covid-19 pandemic on traditional working practices has, however, led some CEOs and politicians to reconsider. But companies dipping their toes in the four-day week model are approaching it in many different ways, with some opting for fewer, but longer, working days and others offering an outright reduction in worked hours.

In October 2022, for example, following calls by the Japanese government for a better work-life balance for its residents, Panasonic introduced more flexibility and a shorter working week for over 60,000 employees in Japan. Among the several options offered by the technology giant, the most popular proved to be the one that allowed employees to compress their working hours into four longer days, for the same salary.

Advertisement

These changes are starting to spread beyond white-collar workers. Sports car maker Lamborghini is planning to introduce more flexible working weeks at a 2,000-strong production site in northern Italy, the first European automotive player to take the plunge. Under the planned approach, workers will be able to alternate four-day weeks with five-day weeks, depending on their shift arrangement. This will result in between 22 and 31 fewer working days a year, with no reduction in salary and with bigger productivity incentives.

Yet, even though Belgium has allowed workers since 2022 to squeeze their working week into four longer days, and Spain and South Africa are currently running state-sponsored trials, the idea is yet to go mainstream. The encouraging results from pilot projects suggest that may change soon. Not surprisingly, employees tend to like the idea. At Italy’s biggest bank, Intesa Sanpaolo, which since January 2023 has offered staff the possibility to work nine hours a day for four days a week, 70% of those eligible, or about 40,000 workers, made it permanent. At EssilorLuxottica, which from April will allow production staff in Italy to work four days a week for 20 days less a year, workers overwhelmingly backed the pilot project.

Advertisement

But bosses ought to also like these arrangements. A 2022 six-month pilot project in the UK showed that the 61 companies that participated, mostly small businesses, had an average increase in revenue of 35% against the June-December 2021 period, although the post-Covid recovery also played a role. At the same companies, 71% of employees reported a decrease in burnout, according to a report by independent research group Autonomy which was partly supported by the University of Cambridge. And the resignation rate fell by 57% compared to the same period a year earlier. In 2022, Unilever extended a four-day week trial to its Australian facilities after a pilot project in New Zealand resulted in lower levels of stress and higher feelings of vigour at work. The Australian pilot was recently prolonged until the second quarter of 2024.

It’s not all rosy. Figuring out an effective rota system while maintaining the same product and service offering may be difficult, especially at small companies. A Sweden 2015 pilot project, which involved six-hour days for four days, had mixed results and drew criticism from right-wing parties that it was not economically sustainable. In the UK, engineering group Allcap abandoned a trial two months before it was due to end because it felt its workers were having fewer, but far more stressful, working days.

Advertisement

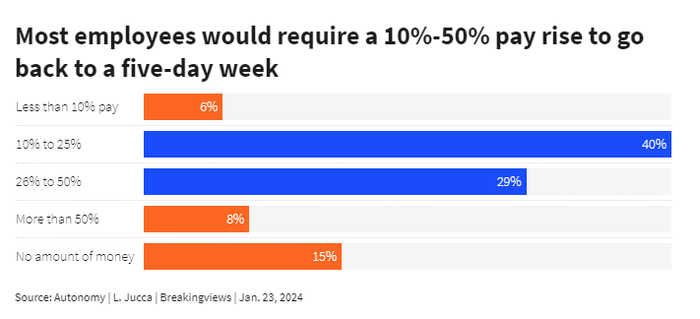

Yet the British SMEs pilot, although based on a small sample, suggests employees are happier to stay with an employer if allowed to work shorter weeks. Around 70% of workers involved in the trial said they would require between 10% and 50% more pay to be persuaded to go back to the full working week or to move to a company that required a five-day work week. This could be an advantage for companies that cannot offer large paycheques to woo talent.

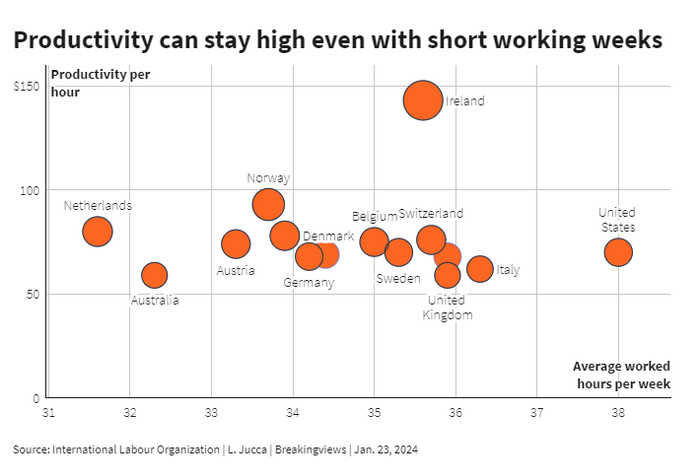

In the end, the biggest benefit may be for the economy. In the Netherlands, where the average working week has already dropped to just 32 hours, GDP per hour, a measure of productivity, is $80, substantially higher than the $59 per hour for a British employee, who works around 36 hours a week on average, according to the International Labour Organization. Germany and Denmark, where weekly hours have dropped to 34, are showing GDP per hour of $68 and $78 respectively. Evidence from a 2021 study on Japan suggests long working hours and overtime hurt team productivity, but this increases when hours are reduced.

Advertisement

That can lead to a further benefit for companies and central bankers: muted wage growth. Normally, workers demand higher salaries when the economy is doing well and they can get better jobs elsewhere. But if favourable working conditions encourage them to stay put, wages and inflation may not spike. Moreover, if workers can earn the same or slightly less by working fewer days, they might have more time to consume. A report by eMarketer shows that 63% of total online retail sales worldwide occur on Saturday and Sunday, when most people don’t work. To be sure, the Panasonic staff who took advantage of more flexible working arrangements said they spent their spare time with, or caring for, family members. But some did say they were happy to carry out activities they liked, or even try a second job.

Artificial intelligence may speed up these trends. If robots and computers can perform more tasks currently carried out by humans, employees may need to spend less time at work. The five-day week is a relatively recent development: in the 19th century, people used to work six days a week and up to 14 hours a day. As technology advances, a further reduction in working days may be warranted.

As the CEO of a consultancy firm in the British trial said: “When you realise that day has allowed you to be relaxed and rested and ready to absolutely go for it on those other four days, you start to realise that to go back to working on Friday would feel really wrong, stupid actually.”

Context News

Sports car maker Lamborghini on Dec. 5 reached a deal with unions to introduce a shorter working week, on certain conditions, for its production workers, the first in the automotive industry in Europe. Under the plan, to start as a one-year pilot by the end of 2024, some workers will alternate a four-day week with a five-day week while others will alternate a five-day week with two four-day weeks, depending on their shift arrangement. Eyewear maker EssilorLuxottica has also agreed to test a four-day week at six Italian factories, for 20 weeks a year. Italian bank Intesa Sanpaolo, which launched the four-day week for most of its workers over a year ago, said 70% of employees involved have decided to keep the arrangement on a permanent basis. Results from a 2022 six-month four-day week trial promoted by campaign group 4 Day Week Global and involving 61 companies in the UK showed that they saw an increase in their average revenues, while 71% of employees reported a decrease in burnout, according to a report. The rate of resignation at these companies fell by 57% compared to the same period a year earlier.

15:01 IST, January 24th 2024