Published 16:24 IST, November 13th 2023

Private equity superstores overstock the shelves

U.S. private equity funds raised some $240 billion in the first nine months of 2023, according to research outfit PitchBook, 13% less than a year earlier.

- Republic Business

- 6 min read

Steady eddies. Private equity investors seem happier these days shopping for returns at specialty shops over supermarkets. In what has been a tough year for fundraising, Clayton, Dubilier & Rice and CVC Capital Partners have accumulated more cash for their flagship buyout funds than peers Blackstone and Apollo Global Management, which oversee a broader range of investment vehicles. It’s one of the first big challenges to the diversified business model typically embraced by publicly listed alternative asset managers.

U.S. private equity funds raised some $240 billion in the first nine months of 2023, according to research outfit PitchBook, 13% less than a year earlier. It’s no shame then that some of the latest flagship buyout vehicles are smaller than their predecessors. The firm led by Steve Schwarzman, for example, said over the summer that it expects its Blackstone Capital Partners IX to end up with “a total size in the low-20s billion-dollar range”, compared with the roughly $26 billion committed to its 8th fund. Apollo boss Marc Rowan, meanwhile, helped close his firm’s Fund X at about $20 billion, one-fifth less than the $25 billion Fund IX.

Two smaller and more narrowly focused investors have defied the slump, however. New York-based CD&R in August raised $26 billion for its 12th-generation private equity fund while Eurocentric CVC managed an even more eye-popping $29 billion in July. It represents the largest buyout fund ever raised, per PitchBook data, while the latest Blackstone and Apollo efforts don’t even make the top five.

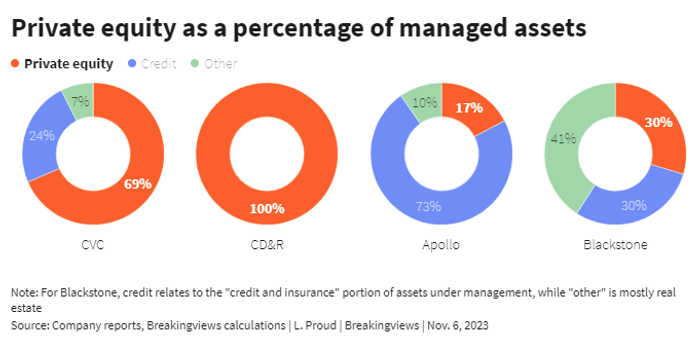

Investors, known in private equity as limited partners, back specific funds for different reasons, which makes it tricky to ascertain what explains the discrepancies. It’s notable, however, that the two clear winners from the 2023 fundraising cycle are rooted in traditional buyouts. The business of buying and selling whole companies accounts for about 70% of assets under management at CVC and it’s all that CD&R does.

For Apollo and Blackstone, private equity has shrunk in significance. Rowan has been transforming his 33-year-old firm, which invests $630 billion on behalf of clients, into even more of a credit and insurance investor. Schwarzman’s shop, whose biggest single asset class is real estate, last month touted more than 70 distinct strategies across the $1 trillion it manages. The founder summed it up last year when he said, “Our customers are constantly in our store and our shelves are full.”

There are various theories about why sprawl may be out of favor this season. One, suggested largely by unlisted firms, is that LPs are starting to mistrust the motives behind diversification. Kingpins like Schwarzman and Rowan care more about keeping their stock prices elevated by accumulating more cash to oversee for a variety of assets, rather than ensuring any single fund does well, or so the theory goes. On this account, savvier investors are flocking to smaller, unlisted buyout shops whose bosses are mostly paid out of fund profit, meaning they share more of an incentive to achieve better performance.

The idea doesn’t entirely stack up, though. For starters, it’s an open secret that CVC has been considering an initial public offering for at least a year. Limited partners clearly didn’t punish the firm over the prospect of senior executives being paid in listed stock. Nor is it true that dealmakers at Blackstone and Apollo are disinterested in creating alpha. While the top brass is paid heavily in shares, fund managers earn most of their fortunes from the profit known as carried interest. In other words, the people running the portfolios are just as interested in returns as LPs, increasingly so as compensation policies tilt toward this more volatile source of income.

A better explanation, from the consultants who advise LPs on where to put their cash, is that private equity supermarkets may be cannibalising themselves. Since raising its then-record-breaking buyout fund in 2019, for example, Schwarzman’s shop has landed $8 billion for a longer-life private equity fund, nearly $7 billion dedicated to Asia and about $9 billion across two investment pools seeking younger, fast-growing firms to back. It’s entirely plausible that some of the money would have otherwise been directed into Blackstone’s flagship fund.

CD&R avoids this risk by only raising one main fund at a time, while CVC is somewhat of a blend. The Luxembourg-based firm led by Rob Lucas separately targets Asia, growth equity and investments that extend beyond the typical five-year time horizon. Even so, the various iterations of its core Europe and Americas fund account for the lion’s share of CVC’s private equity assets, according to its website.

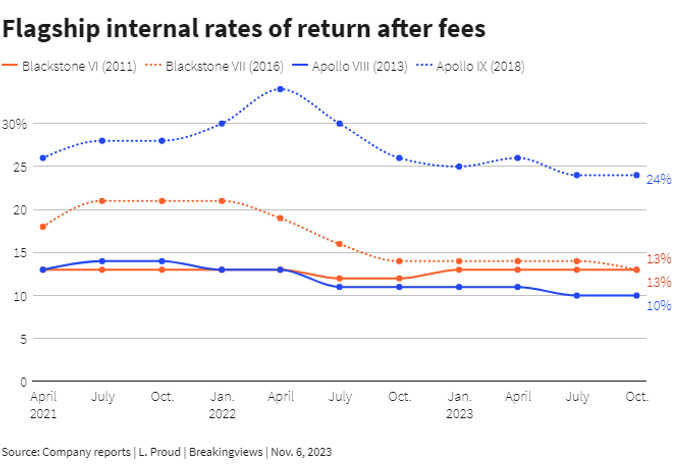

A third possibility, and perhaps the most troubling for Schwarzman and Rowan, is that the superstores’ flagship funds don’t always deliver leading returns. Blackstone’s sixth and seventh flagship buyout funds, which started investing in 2011 and 2016 respectively, both had generated a 13% internal rate of return, after deducting fees, as of Sept. 30. The eighth-generation fund, which has been writing checks since early 2020, is running at a 12% net IRR.

Those figures are admittedly better than the 11% earned by U.S. pension funds on their private equity investments between 2000 and 2021, according to a study by alternative investments adviser Cliffwater. But they’re still below the roughly 15% net IRR that buyout dealmakers typically target. Apollo’s performance, meanwhile, has been more erratic. Its eighth fund, a 2013 vintage, had a disappointing 10% net IRR as of Sept. 30, while the 2018 Fund IX is at 24%, on paper.

The numbers are patchier for unlisted CVC and CD&R. The Calpers private-equity performance database shows the European firm’s 2014 and 2018 vintages generated respective net IRRs of 18% and 23% as of December 2022. Limited partners may reckon that such consistent outperformance implies that Lucas has found a repeatable formula. The same data gives CD&R’s 2018 fund a stellar 39% net IRR, which would explain why investors were keen to plough money back into its successor.

These results suggest there’s no clear, consistent edge from stocking everything from credit to infrastructure. Until they can prove otherwise, the more scattered private equity superstores risk losing more ground to the specialists. After all, the flagship funds are starting to look like just another product on their shelves.

Context News

Apollo Global Management said on Nov. 1 that its Fund X buyout fund had invested about $3 billion of the roughly $20 billion it had raised earlier in the year. The company’s previous flagship private equity fund started investing its $25 billion of committed capital in 2018 and had generated a 24% internal rate of return after fees, as of Sept. 30.

Updated 16:24 IST, November 13th 2023