Published 14:44 IST, March 26th 2024

Lower taxes would cripple Europe’s growth

Political leaders in the European Union and the UK face a daunting task for green transition, boost defence spending.

- Republic Business

- 6 min read

Raise’m up. Europe’s impoverished governments must increase public investment by up to 3% of their collective GDP annually in the coming years. Yet some politicians still think they can promise voters lower taxes. Since more debt and spending cuts won’t be enough to fund the economy’s future needs, fewer fiscal revenues now can mean slower growth later. Governments must choose between political expediency and economic realities. The latter suggest that higher taxes will be needed.

Political leaders in the European Union and the UK face a daunting task. They must invest in the green transition, boost defence spending to deal with new threats and help renovate telecom or railroad infrastructure. That’s before they turn to the business of boosting spending on healthcare to look after an ageing population.

The numbers are scary. Implementing the European Commission’s “Green Deal” will necessitate investments of some 600 billion euros a year until 2030. If governments fund about half that amount, with the other half coming from private investors, that will be about 1.7% of the region’s GDP. In the UK, a good yardstick is the opposition Labour Party’s pledge to spend an extra 28 billion pounds a year on the green transition. It has since rowed back on the promise, but it provides a rough idea of the British economy’s environmental needs – about 1% of GDP.

The EU and the UK also need to keep investing more in their military. Europe’s NATO members only reached last year the goal of spending 2% of GDP a year on defence they had originally agreed on in 2006. But that was only catching up with years of declining military spending. Some experts estimate that preparing for future threats means investing in defence another 1% of GDP, the equivalent of more than 240 billion euros a year when including the UK.

Infrastructure spending will add to the bill. Upgrading telecommunication networks alone would cost the public purse some 20 billion euros a year if governments fund just half of the programme outlined by Brussels. In the UK, future governments will have to increase spending on essential works by at least 10 billion pounds a year, according to a National Infrastructure Commission report.

In all, these new investments would amount to 2.7% of the EU and UK’s combined GDP, according to Breakingviews calculations. That’s not counting the need to invest in education and training, to help workers deal with ongoing technological changes, and the increasing resources needed by the healthcare sector to cope with an ageing population. To meet all new public investment needs, 3% of GDP looks like a conservative estimate.

Governments have only three ways to finance this. They can borrow more. But some, such as France and Italy, already pay more in interest and principal repayments than on primary education or domestic security. Italy’s government gross debt should amount to 143% of the country’s GDP this year, according to the International Monetary Fund. France’s is at 110%, and the UK’s at 106%. With yields on government bonds at multi-decade highs, more borrowing would test market confidence. Germany is the only major European power that could afford that path, with debt at only 64% of GDP after years of fiscal restraint and declining public investment. But it does not want to do so for deeply ingrained political reasons.

Spending cuts could also in theory help free up resources. French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire sounded almost heroic last month when he announced 20 billion euros of savings for next year – but that’s just 0.7% of France’s GDP.

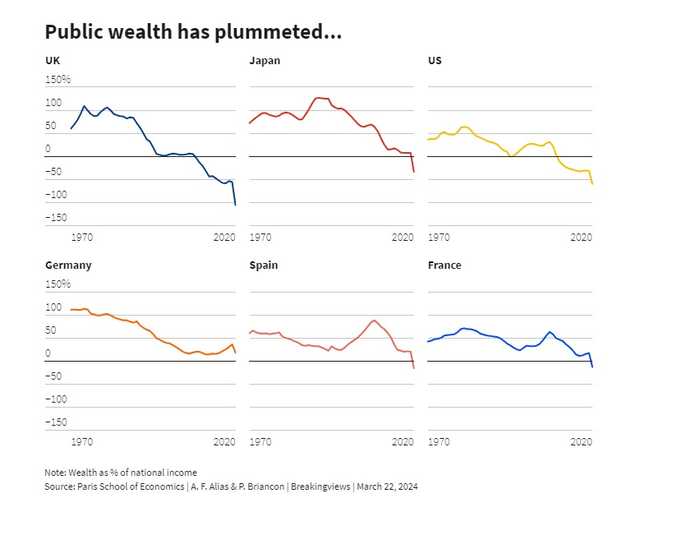

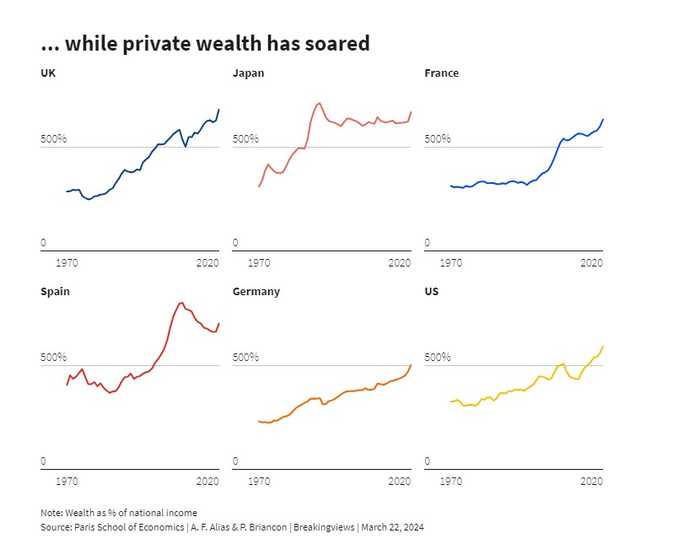

That leaves taxes. Governments here are faced with an unprecedented situation. They have never been so destitute while facing such financing needs. As private wealth accumulated in the last few decades, governments became poorer. According to the Paris School of Economics’ World Inequality Report, in rich countries, the government’s share of the national wealth – the sum of all financial and non-financial assets, minus debt – has declined to nearly nothing. European governments held between 20% and 30% of their nations’ wealth in the 1980s. They only own 2% now. Most of the fall of government wealth has been due to the rise in debt.

Yet politicians like UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, French President Emmanuel Macron and the German three-party coalition led by Chancellor Olaf Scholz have pledged, or are still pledging, not to raise taxes. The problem is that the tax burden is already high. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, it has increased in member countries by a little less than 2 percentage points, to 34% of GDP, in the two decades ended in 2022. Over the same period, it rose by around 4 percentage points of GDP in the UK, to 35%, and in France, where it tops 46%.

Any rise will have to happen within a major redistribution effort, with higher taxes on the richest financing subsidies for the poorest. The green transition, for example, requires governments to help lower-income families switch to electric cars or heat pumps. Energy bills will also have to be subsidised. In the corporate world, companies will need incentives to invest in climate-friendly technologies. Meanwhile, public finances will be affected by the phase-out of the significant receipts from fossil fuel taxes.

The fiscal mix of the future will vary from country to country. Wealth taxes that include financial assets will be difficult to implement because they would need an international agreement to prevent capital flight. Taxing the rich will, however, be crucial for governments to be able to show that the burden will be fairly shared. An overhaul of inheritance taxes, which in most of Europe the wealthiest can escape through multiple loopholes, would be an important step. And a serious implementation of the international agreement on the minimum rate for corporate taxes would bring in more than 115 billion euros in the EU and the UK in new tax revenue, according to the EU Tax Observatory.

European governments are faced with a simple choice. The easiest way out of the quandary would be to cut public investment plans, as Labour did in Britain. But lower public investment will harm the economy in the future. Businesses need solid energy grids, good transport infrastructure, fast and reliable networks, and well-trained and healthy workers. Failing to invest today will mean lower growth in the long term.

Updated 14:44 IST, March 26th 2024