Published 17:37 IST, March 29th 2024

Shein’s fast fashion comes with fast-finance risks

While Shein serves everything from sub-$40 tuxedos to jewelry in the shape of fried chicken.

- Republic Business

- 6 min read

Sew emotional. For a sign of how the internet has changed the way consumers shop for clothes, consider the “Shein haul.” It’s a social media happening where customers of the eponymous retail app shake out a big box of low-priced goods and sift through the contents. Some items are keepers; some are not. The element of surprise is arguably a thrill for fashionistas. For investors trying to work out whether Shein is worth around $50 billion or potentially quadruple that, the uncertainty is less welcome.

The Singapore-based company is itself a kind of surprise. It came from nearly nowhere to capture a sizeable share of the market known as “fast fashion” thanks to low prices, speedy design and delivery, and smart use of influencers. Shein’s suppliers are mostly in China, but its customers are largely in the United States. Already its global sales, which people familiar with the situation say were more than $30 billion last year, are closing in on the $39 billion made last year by old-school fast-fashion champ and Zara owner Inditex.

While Shein serves everything from sub-$40 tuxedos to jewelry in the shape of fried chicken, one item not yet for sale is the company’s own stock. That could change, if an initial public offering in New York gets the go-ahead from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the agency’s Chinese counterpart. London is a potential fallback, as is Singapore. Either way, it’s a good time for would-be investors to size up the company.

At first glance, Shein looks just like an online retailer. But that’s deceptive because the company really trades data. It gathers information on how consumers browse and what flicks their switches, in a feat of behavioral analysis analogous to the algorithm that powers short-video app TikTok. It then serves up that information to around 5,000 manufacturers, who can create small-batch products sold on Shein’s platform. Unlike a traditional retailer, it lacks the burden of mass production, a network of physical stores, or piles of unsold clothes.

Shein discloses little financial information about its business. If the company can keep expanding revenue at the current rate of around 40%, however, its top line could be huge. Clothing and footwear sales are on track to be about $1.3 trillion in the world outside China in 2025, according to Euromonitor International data. If the company can capture 5% of that – roughly the same share that sneaker supremo Nike has in the U.S. – revenue would be over $60 billion.

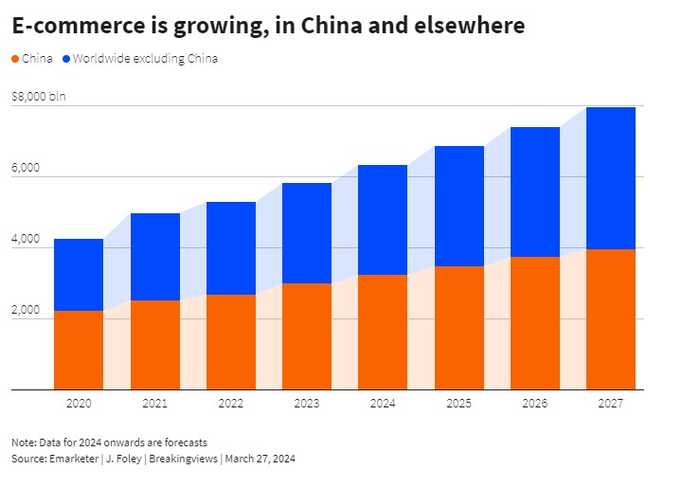

For now, Shein is focused on fashion. But its offering of “supply chain as a service” – based on getting real-time data on customer tastes straight to manufacturers – could apply to other products. Global e-commerce sales are headed for around $3.4 trillion outside China this year, according to eMarketer. If Shein captured 5% of that its top line would be closer to $200 billion. At a 10% net profit margin – midway between Inditex and Amazon.com AMZN.O – Shein would be making around $20 billion a year. On a not-very-ambitious multiple of 10 times, the company would be worth $200 billion.

A fundraising last year that valued the company at around $66 billion suggests investors are applying a hefty discount to such assumptions. Shein’s powerful detractors justify some skepticism. French parliamentarians approved a bill in March to penalize clothing companies that produce landfill-bound fashions. A tax loophole that allows small-value packages sent from outside the United States to avoid import levies may close – as Shein has acknowledged.

Temu, another turbo-charged online retailer owned by Chinese-founded technology giant PDD, is another threat. It has grown even faster than Shein, amassing roughly the same U.S. revenue in fewer than 18 months, according to Euromonitor, albeit by selling products other than clothing. If the rivalry intensifies, Shein might have to sacrifice some margin to defend its turf. With profitability of just 3%, say, that $66 billion valuation would look fitting. And the fight could backfire on both. Some members of U.S. Congress claim Shein and Temu are “building empires.”

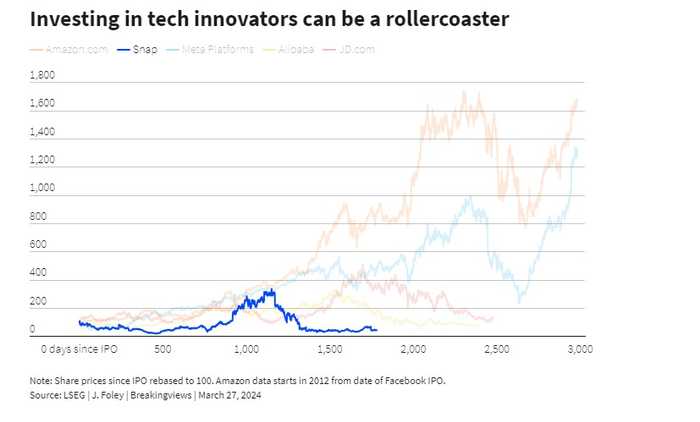

One important question for IPO investors is what Shein will look like years from now. For new and fast-growing companies, that’s almost impossible to answer. Amazon, once a retail marketplace, now also runs computer cloud services and owns movie theaters. Facebook owner Meta Platforms has plowed billions of dollars into building the so-called Metaverse, a concept that would have been totally alien to buyers of its IPO stock in 2012.

Amazon and Meta have continued to reward shareholders. Alibaba offers a more cautionary tale. China’s dominant e-commerce company went public in New York in 2014 with a valuation of around $160 billion and dreams of becoming the world’s biggest data-sharing platform. Its market value quadrupled and then fell back to $200 billion, the victim of overexpansion, diversification into bricks-and-mortar retail, fierce competition, and political frictions.

The company founded by Jack Ma is very different from Shein. Its typical customer is firmly in China, while Shein’s are everywhere else. Ma courted the limelight, while Shein founder Sky Xu keeps a low profile. Nonetheless, both share a goal of becoming data-focused intermediaries between many small suppliers and billions of consumers. Alibaba parlayed its data into offering financial services, and complex logistics hubs. Shein could also evolve in unforeseen ways.

For now, the company’s biggest strength is probably its lack of physical assets and inventory. Ride-hailing app Uber Technologies and home-sharing service Airbnb show investors reward lean balance sheets. But once-svelte companies can gain weight with age. Amazon’s total assets have risen tenfold in a decade; Alibaba’s have increased by a factor of nearly 30 over the same time. Despite its youth, Shein has already made some strategically odd acquisitions, including troubled UK brand Missguided and a stake in U.S. retailer Forever 21. A bigger swerve into bricks and mortar would dim Shein’s allure.

Those will be the kinds of questions Xu and Chairman Donald Tang would face if an IPO moves from sketch book to factory floor. As many fallen tech stars have shown, the faster a company’s rise to greatness, the harder it can be to map out its future. Shein’s challenge therefore is to retain the nimbleness of fast fashion, without sacrificing the timeless look that investors prize: being both profitable and predictable.

(Additional reporting by Anshuman Daga)

Updated 17:37 IST, March 29th 2024