Published 16:03 IST, January 26th 2024

Abu Dhabi’s Europe M&A hedges an opaque future

The way Exxon Mobil, Shell, Saudi Aramco and ADNOC shape up in 2050 remains the key.

- Republic Business

- 6 min read

Chemical Brothers. Sultan al-Jaber is in the middle of an M&A splurge. The chief executive of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) is readying $40 billion of European deals in the field of gas-guzzling petrochemicals, less than two months after overseeing a global deal to transition away from fossil fuels as head of the COP28 climate negotiations in Dubai. The former offers a promising hedge against the successful delivery of the latter.

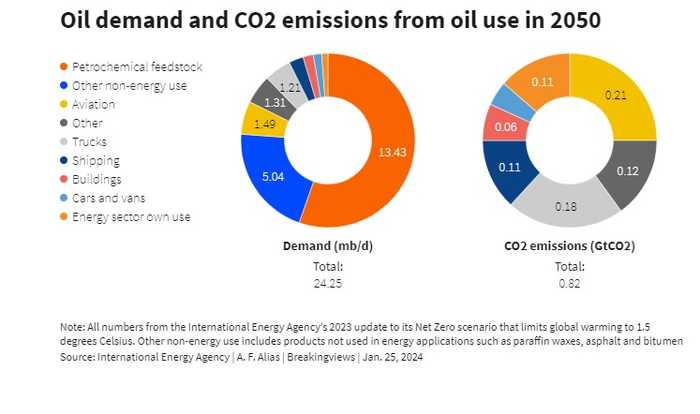

One of the key uncertainties surrounding both private oil majors like Exxon Mobil and Shell, and national oil companies like Saudi Aramco and ADNOC, is what their businesses are going to look like in 2050. To keep global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times, daily oil demand needs to fall from 100 million barrels to around 25 million barrels by mid-century, the International Energy Agency reckons. If anything like that transpires, lots of oil companies are going to need a Plan B.

The cynical strategy for drillers would just be to hope the climate change fight fails, oil production stays near its current level up to 2050, and affordable but as yet non-existent technology emerges to capture the emissions of greenhouse gases. While UK driller BP is devoting an increasing volume of its capital expenditure to low-carbon businesses, most oil majors lack meaningful transition plans. U.S. giants Exxon Mobil and Chevron are doubling down on oil via chunky domestic acquisitions.

The United Arab Emirates, which wants to actually grow daily crude production from under 4 million barrels to 5 million barrels by 2027, has arguably a more constructive way to stay in business. It’s focusing on the section of oil demand that will still be around in 2050, even in a decarbonised world.

Over half of the 25 million barrels a day potentially consumed by then will be deployed as the raw material for petrochemicals – the use of fossil fuels to manufacture plastics, agricultural fertiliser and various other types of specialty chemicals. That 14 million barrel a day level by 2050 should remain roughly what it was in 2022, the IEA says, even as oil for petrol-fuelled cars becomes redundant. The key difference between gasoline and plastics is that users burn the former, but not the latter. Plastics therefore have much lower “Scope 3 emissions”, which are a huge part of the climate change headache – around 90% of the carbon emitted by the oil sector comes from customers burning oil products, rather than via the process of extracting the black stuff.

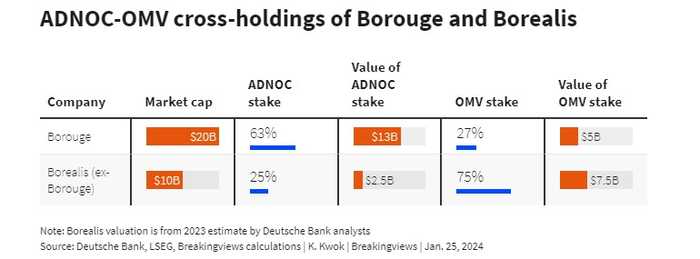

That’s why ADNOC has been mulling a $30 billion merger of Abu Dhabi-listed Borouge, in which it holds an overall stake of 63%, and Austria’s Borealis, in which European oil group OMV has a majority shareholding. The combined entity would be a world leader in the production of polyolefin, used to make plastics that surround power transmission cables connecting wind farms, and also to shield medical devices like inhalers. Borealis makes the chemical particles, and Borouge brings among other things cheaper input costs to the table.

But Jaber’s M&A doesn’t stop there. Before Christmas he paid Dutch group OCI $3.6 billion to acquire its stake in Fertiglobe, which gives ADNOC more control of an Abu Dhabi-listed group that is a key producer of urea and ammonia used to enhance crop production. He continues to sniff around Germany’s $8 billion Covestro, which makes specialty chemicals used for coatings and foam to stuff car seat cushions. The ADNOC boss even expressed interest in $11 billion Wintershall Dea prior to the German oil and logistics company’s merger with Harbour Energy in December, and made a $2.1 billion offer to acquire a major stake in Covestro’s rival in Latin America, Braskem.

There’s a basic logic to bulking up in the supply chain of petrochemicals. Furniture, medical devices and car parts made out of plastics and synthetic rubber may increasingly require less oil and gas – Borouge, for example, is working on ways to recycle plastics over time. But demand for them is likely to persist. Owning more of that capacity offsets some of the loss of revenue from selling crude ultimately used to make petrol.

Even so, the M&A flurry doesn’t automatically guarantee ADNOC a stress-free future. In order to stick with his intention to reduce ADNOC’s emissions from its own production processes to net zero by 2045, Jaber would have to find a way to decarbonise his new acquisitions too. That hinges on chemical recycling technologies which companies like Covestro are developing with academia, but these are still at a relatively early stage.

Meanwhile, ADNOC would struggle to replace all the revenue it currently makes from selling crude around the world by flogging petrochemicals. While the unlisted UAE giant doesn’t disclose group financial data, one very rough proxy is Exxon Mobil, which produces around 4 million barrels of oil and gas a day. In 2022 Exxon generated over $410 billion of revenue. If ADNOC bought Fertiglobe, Covestro and a merged Borouge and Borealis, that entity would in the same year have only had sales of around $45 billion.

Still, relative to historical levels chemicals companies are trading at a huge discount. After enduring high energy costs after the Russia-Ukraine war, petrochemicals demand remains weak because customers are still drawing down from excess stocks accumulated in two years of supply chain disruptions. On average the global chemical industry is trading at 8 times EBITDA, compared to 13 times in 2019, using LSEG data, and analysts at Barclays expect chemical prices to stay below their long-term averages this year.

There’s one other driver: politics. On the face of it, European politicians have become increasingly wary of overseas investors owning key bits of its domestic industrial base like Borealis and Covestro. Yet German and Austrian politicians have also struck gas supply deals with the UAE, and see it as a meaningful partner to replace Russian gas that’s no longer flowing to the continent. How big a factor this is will be seen in how much control OMV-dominated Borealis retains as and when it’s spliced together with UAE-controlled Borouge. But on the face of it Abu Dhabi’s pitch for a big slice of European infrastructure is one piece of cross-border investment that shouldn’t end up on the scrap heap.

Updated 16:03 IST, January 26th 2024