Published 21:57 IST, January 10th 2024

Narrow exits will fatten fattest buyout fat cats

Buyout firms have been struggling to offload portfolio companies

- Republic Business

- 3 min read

Survival of the fittest. The queue to exit is getting long in private equity. Buyout firms have been struggling to offload portfolio companies, with initial public offering and M&A markets clogged by higher interest rates and valuation mismatches. Many probably will soon be forced to accept discounted prices, which will make the industry’s richest even richer.

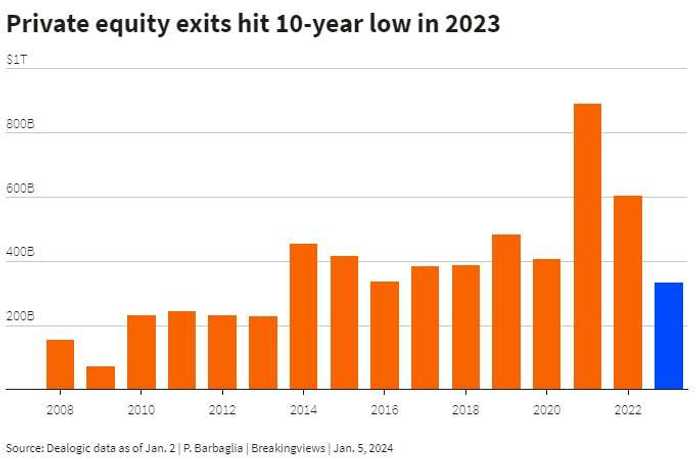

A record $2.8 trillion of unsold assets in mid-2023 – four times as much as during the 2008 global financial crisis, according to a study of consultancy Bain & Company – has delayed returns of capital to investors. There were only $333 billion of so-called exits last year, a decade low, research outfit Dealogic reports. Yet buyout firms raised about $400 million per fund on average last year, roughly twice as much as in 2021 when more than 5,000 new funds were raised as opposed to nearly 2,000 last year, according to data firm Preqin.

The struggle is taking a toll on some more than others. London-based Bridgepoint, which owns Burger King franchises in Britain and France, last summer warned it would take longer to sell some investments and to raise 7 billion euros for its latest flagship fund. The $2.6 billion London-listed investment firm is now expecting to complete its fundraising in the first quarter of 2024. And although its shares rallied in November and December, they’re trading more than 25% below their market debut price in July 2021. By comparison, Sweden’s EQT said recently it had nearly 20 billion euros of fee-generating commitments for its 10th buyout fund, despite having sold only nine out of 17 holdings in its seventh fund, from 2015.

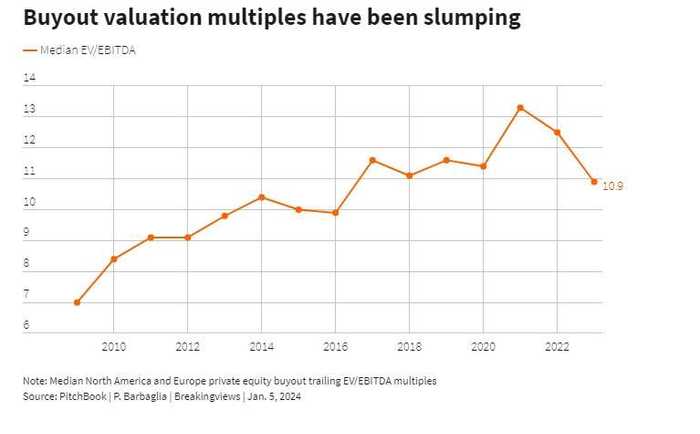

A window may be opening as investors anticipate a dip in borrowing costs. But private equity deal multiples have yet to find a bottom. In North America and Europe they are down to an average of less than 11 times EBITDA for the past 12 months from a peak of more than 13 times in 2021, according to data provider PitchBook. Trickier businesses, such as the margarine and spreads business KKR agreed to buy in 2017 for 6.8 billion euros, will have to see if other IPOs can squeeze out first or hope animal spirits will reinvigorate acquisitive corporate chieftains. Stronger firms will sit tight or be creative, as EQT was when it privately sold a $1 billion stake in Galderma last year instead of just waiting to take the skincare company public.

Meanwhile, the growing list of assets seeking new homes is also likely to put downward pressure on valuations. Some buyout barons will have to grin and bear it to appease restive investors, even if it causes these private equity have-nots to lose more ground to the haves. The top 25 firms, which include Apollo Global Management and KKR, have become more dominant, claiming 22% of the $2.5 trillion raised, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence. That’s up from 17% of the available dry powder a decade ago, Preqin’s data shows. The Darwinians are at the gate.

Updated 21:57 IST, January 10th 2024