Published 13:31 IST, April 21st 2024

Shell’s value gap is more strategy than geography

All big oil groups produce a fungible commodity which trades in a global market.

- Republic Business

- 6 min read

No quick fix. It is generally a good thing when a chief executive worries about his company’s share price. The danger is seeking superficial fixes. Ever since Shell CEO Wael Sawan took charge last year, he has made it his mission to close the $230 billion oil giant’s valuation gap with U.S. rivals like Exxon Mobil. If his efforts fail to produce results by 2025, however, he has threatened to consider “all options” including shifting the UK-based company’s primary listing to the United States, he told Bloomberg last week. The problem is that Shell’s value gap is due to more than just geography.

Sawan is not alone in wondering whether his company’s domicile is weighing on its value. In the past few years, a growing band of companies, including plumbing parts specialist Ferguson and online gambling group Flutter Entertainment have switched their stock market listings from London to New York in search of a different shareholder base and higher multiples. A transatlantic switch for Shell would be on a different scale, though: it is currently the largest company listed in the United Kingdom, accounting for over 9% of the benchmark FTSE 100 Index.

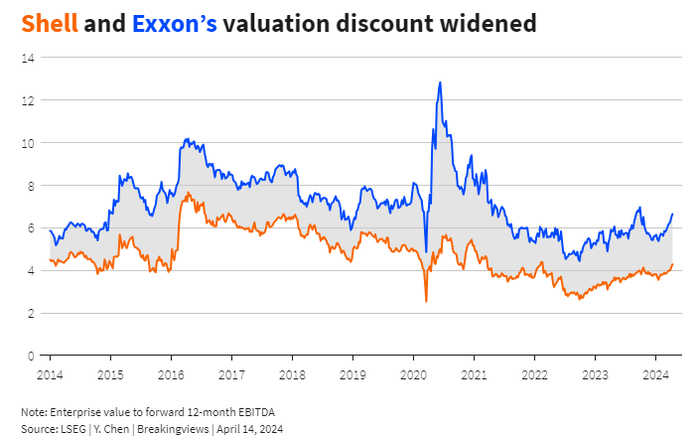

It is easy to understand Sawan’s valuation frustration. All big oil groups produce a fungible commodity which trades in a global market. And though European groups including Shell have traditionally traded at a discount to U.S. oil giants, the gap has widened in recent years. In 2018, for example, Shell’s value including debt was around 6 times expected EBITDA for the next 12 months, according to LSEG data, while Exxon was valued at 7 times. The European group now trades at a 4 times multiple, while its $470 billion U.S. rival is on 6 times.

To explain the difference, start with strategy. In the past few years, oil groups have faced mounting pressure from investors and regulators to diversify their businesses and prepare for declining demand for the black stuff. But while many European executives acknowledged a future with less oil, American bosses like Exxon’s Darren Woods have been less willing to shift.

Ben van Beurden, Sawan’s predecessor at Shell, invested heavily in the energy transition, pouring cash into wind and solar power, biofuels, hydrogen, and charging points for electric vehicles. While his successor has pulled back from renewable energy as higher interest rates depressed returns, Shell still invested around 20% of its cash capital spending on low-carbon assets in 2023. By contrast, Exxon spent about 2% on low-carbon solutions that primarily focused on capturing and storing carbon emissions.

Differing priorities in allocating capital are also evident in oil, which remains the companies’ most lucrative activity and their main source of earnings. In 2021, Shell decided to aim for an expected reduction in oil production of around 1% to 2% each year until 2030, including divestments and the natural decline of existing oil fields. While Sawan retired that goal last year, he still expects Shell’s total oil and gas production in 2030 to be roughly the same as in 2022.

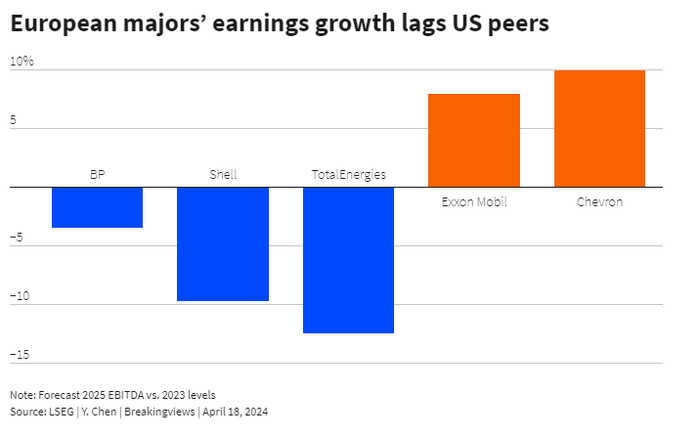

Meanwhile, Bernstein analysts expect Exxon’s total production to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 6% over the same period. The analysts expect Exxon’s oil output alone to grow at a 7% compound rate thanks to investments in Guyana and its recent $60 billion takeover of Pioneer Natural Resources, which boosts growth in U.S. shale. As a result, analysts expect Exxon to report EBITDA of $80 billion in 2025, 8% more than last year, while Shell’s EBITDA will decline by 10% over the same period, according to forecasts compiled by LSEG.

This divergence matters to investors in oil companies because earnings underpin those companies’ ability to pay dividends and buy back stock. European groups have proved themselves less dependable on this front by slashing payouts after oil prices collapsed during the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2020, Shell more than halved its annual dividend to $7 billion; Exxon kept its distribution to investors steady at $15 billion.

Companies like Shell and its British rival BP have also been less strategically consistent. Under van Beurden, for example, Shell planned a big push into chemical products, only to unwind many of those investments due to poor returns.

While Sawan has focused on cutting costs and improving shareholder returns, investors are so far not giving him much credit. Shell’s free cash flow yield – the cash a company generates after capital spending, divided by its market value – is currently 12%, against 7% for Exxon, LSEG estimates show.

It is true that European oil companies face other specific factors that lessen their attraction in the eyes of investors. The continent generally has more punishing taxes for fossil fuel producers, while its lenders are more reluctant to finance oil groups.

Still, on balance switching Shell’s listing to the United States would not close the valuation gap. Indeed, the company’s highly liquid stock can easily be bought by U.S. fund managers in London or through American Depositary Receipts traded in New York. While Shell’s shareholder structure is highly fragmented, among its top 100 investors – who hold around a third of the company’s stock – over 40% is already held by U.S. investors.

One transatlantic difference is that U.S. investors have in recent years cooled on allocating capital according to environmental considerations, while European money managers are still more likely to consider a company’s green credentials. If Sawan wanted to shift Shell’s strategy more aggressively in the direction of pumping more oil, he might therefore find a more receptive investor base in the United States.

However, tapping into those investors would require a big effort and considerable risk. In order to be eligible for U.S. benchmarks like the S&P 500 Index, Shell would not only have to move its primary listing stateside, but also shift its head office and senior executives. The company would have to switch from international to U.S. accounting standards. And Sawan would have to persuade three-quarters of Shell’s current shareholders to approve the move, even though index-tracking funds would be forced to sell when the company dropped out of the FTSE 100 benchmark. The benefits of moving would also take time to flow through. For example, the $43 billion Ferguson, which moved its primary listing to the United States in 2022, is still waiting to join the S&P 500 Index.

Sawan’s frustration with his company’s valuation gap is understandable. But the reasons for the divergence defy a superficial fix.

Updated 13:31 IST, April 21st 2024