Published 19:10 IST, October 30th 2023

Israel war tests US appeal to global swing states

Joe Biden emphasises the importance of the rule of law to distinguish the United States from Russia and China in addressing international issues.

- Opinion

- 6 min read

Swing state strategy. Joe Biden has sought to portray the United States as a superpower that cares about the rule of law. The American president says this distinguishes it from Russia and China. He has made a principles-based case for pushing back against Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and Chinese President Xi Jinping’s sabre-rattling vis-à-vis Taiwan.

The Gaza conflict, which has moved into a new phase as Israel stepped up its ground operations in recent days, is challenging that narrative. The mounting number of civilian deaths in the Palestinian territory may not just erode Israel’s global support, as former U.S. President Barack Obama argued last week. The standing of the United States, especially among so-called swing states – influential countries that are being wooed by both the U.S. and the People’s Republic – is also at stake because of its strong support for Israel. That could weaken it in the new Cold War with China.

Biden has sought to draw parallels between Hamas’ brutal attack on Israeli civilians earlier this month and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine by saying that both challenge the rules-based world order. This argument has some traction in parts of the world, especially rich democracies.

But many developing countries don’t see it that way. Some, including Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia and mainly Muslim ones such as Indonesia have criticised Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories. Meanwhile, Queen Rania of Jordan has accused the West of a “glaring double standard” for condemning Hamas’ attacks on Israeli civilians while only expressing concern for Palestinians who died as a result of Israeli shelling.

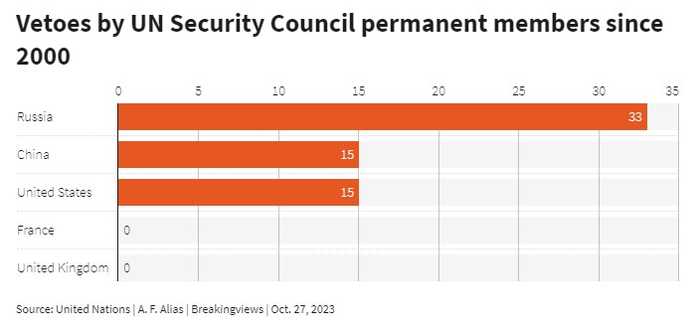

The United Nations General Assembly voted on Friday by 121 to 14 for a humanitarian truce to deliver aid in Gaza, with the U.S. one of the few countries joining Israel in opposing the non-binding resolution. Washington had the previous week vetoed a similar resolution at the more powerful UN Security Council. That marks a contrast from the situation last year when the U.S. was part of large majorities in the General Assembly that condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, after Moscow vetoed resolutions in the Security Council.

Multipolar world

The U.S. has vetoed many Security Council resolutions which Israel objected to over the decades. So the fact that it has done so again may seem like business as usual.

But if accusations of double standards stick, the United States will suffer more than in the past because it is facing increasing challenges from an economically powerful China and a revanchist Russia. This is the challenge Biden was referring to when he said this month that the U.S. is facing an “inflection point” in international relations.

What’s more, swing states – which back neither the United States nor China – have more power than they did during the old Cold War between the West and the Soviet Union. Members of what was called the non-aligned movement had little clout in that era. But countries such as India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and Brazil are increasingly economically important. As a result, there is now a multipolar world.

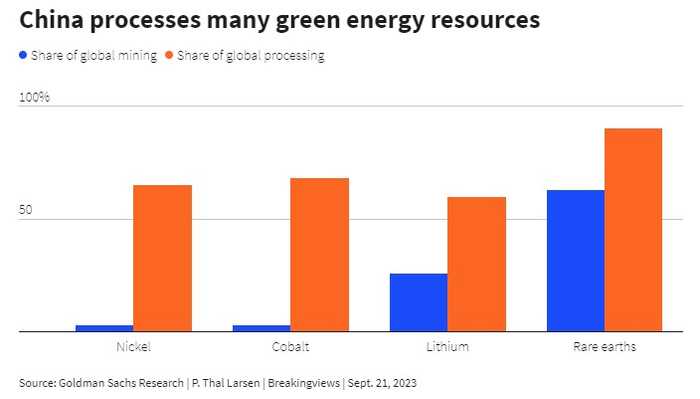

The United States needs good relations with these countries in part for military reasons but mainly for economic purposes. As it seeks to wean itself off excessive dependence on China, it needs alternative sources of critical raw materials and new suppliers of manufactured goods.

Jake Sullivan, the U.S. National Security Advisor, explained last week that a key source of the country’s power was its “latticework” of alliances across the world. While most countries will of course determine their relations with the U.S. on the basis of self-interest, values play a role.

The Israel-Hamas war has already put on ice U.S. plans to normalise relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel – a move that, among other things, could have countered growing Chinese influence in the Middle East. The conflict has also caused new friction with Turkey, a NATO ally, whose President Tayyip Erdogan said earlier this month that the U.S. moving an aircraft carrier closer to Israel would lead to a massacre in Gaza.

Even before the conflict, the U.S. had failed to gain the support of some key swing states such as India and South Africa in condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It may struggle even harder to woo developing countries in the future.

War and peace

The United States seems to appreciate these risks. This may be one reason it is putting increasing pressure on Israel to follow the “law of war” – a series of laws about what is and is not permitted in a conflict – and let much more humanitarian aid flow to Palestinian civilians in Gaza.

Biden also spoke last week to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu about the importance of a “pathway for a permanent peace between Israelis and Palestinians” after the crisis. The U.S. is backing a two-state solution, which envisions an independent Palestinian state alongside Israel.

Such pressure may convince some countries that the United States is pursuing a principles-based foreign policy in the Gaza conflict. But others will consider it too little, too late – particularly given U.S. arms supplies to Israel and its own long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, says Mustafa Kamal Kazi, a former Pakistani ambassador to Russia and Iraq.

If aid flows to Gaza in sufficient quantities to avoid a much worse humanitarian catastrophe, Biden may get some credit. Making progress on a more permanent peace between Israelis and Palestinians would also advance U.S. interests and burnish the U.S. president’s reputation.

But this is a tall order. Not only is Netanyahu opposed to the two-state solution; it’s unclear who will govern Gaza if Israel succeeds in its goal of dismantling Hamas. What’s more, it will be hard to create a viable state in the West Bank, the other Palestinian territory, in part because so many Israeli settlements are there.

Jonathan Cohen, a former U.S. ambassador to Egypt, sees a pathway. He argues that Netanyahu will probably no longer be prime minister after the conflict and points out that a more centrist Israeli government would probably be more open to a two-state solution. He also says that, in the context of a two-state solution, it may be possible to arrange a limited land swap, where Israel gives territory to the West Bank in exchange for keeping its largest settlements there.

The Israeli war may last a long time and its aftermath may be tortuous. How it evolves matters most to the people living there. But it could also have an important impact on the United States’ influence with swing states and its struggle with China.

Updated 19:10 IST, October 30th 2023